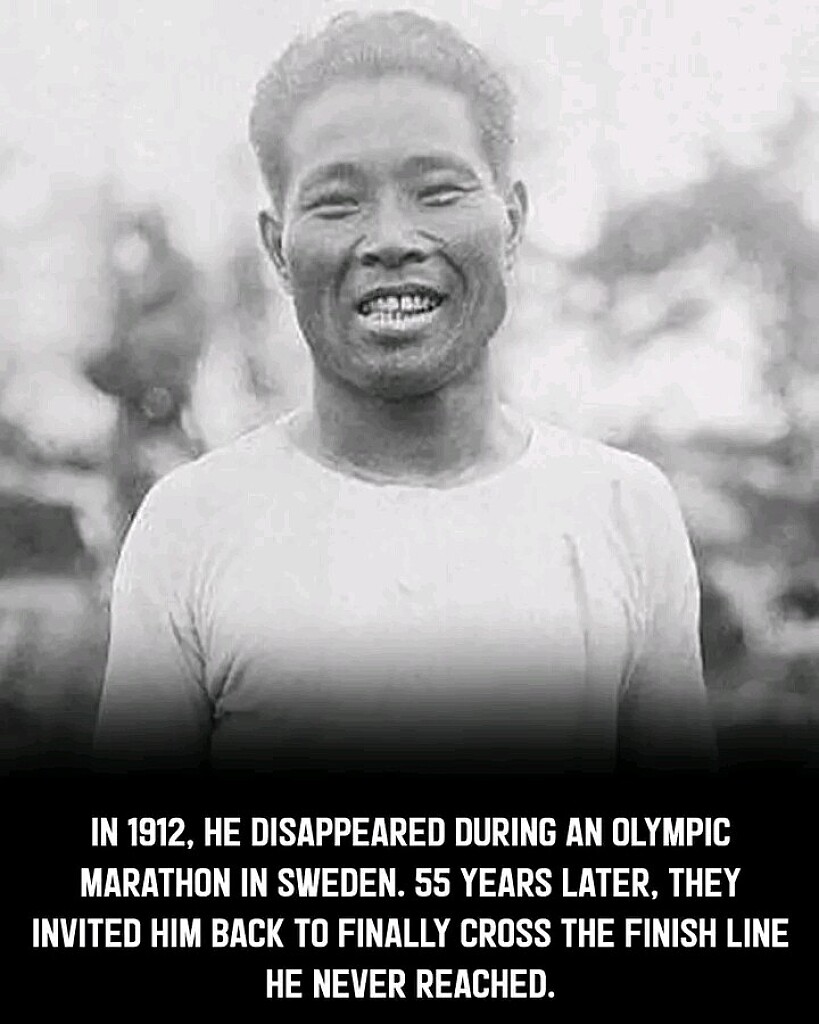

In 1912, he disappeared during an Olympic marathon in Sweden. 55 years later, they invited him back to finally cross the finish line he never reached.

July 14, 1912. Stockholm, Sweden.

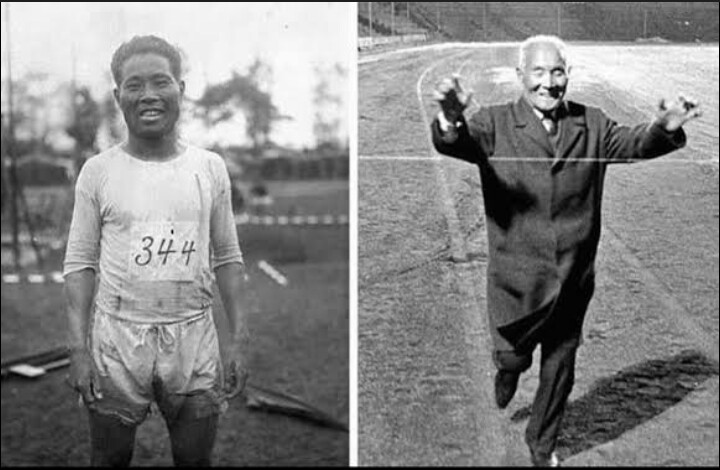

Shizo Kanakuri stood at the starting line of the Olympic marathon, representing Japan for the first time in Olympic history. He was 20 years old, a distance running prodigy from Kumamoto, and he carried the weight of an entire nation's expectations on his shoulders.

Japan had never sent an athlete to the Olympics before. Kanakuri wasn't just competing—he was introducing Japan to the world stage of athletics.

And he was legitimately fast. He had recently set a world record for 40 kilometers with a time of 2 hours, 32 minutes, and 45 seconds. He wasn't just there to participate. He was there to compete.

The marathon course wound through Stockholm's streets and countryside—42 kilometers of roads, paths, and summer heat.

And it was hot. Brutally hot. The temperature climbed to 32 degrees Celsius (about 90°F)—scorching for Sweden, devastating for marathon runners.

Sixty-eight runners from 19 countries lined up. The largest Olympic marathon field in history at that time.

The gun fired. They ran.

From the beginning, the heat was merciless. Runners struggled. Some dropped out within the first hour. Others collapsed on the course.

Kanakuri started strong, running near the front of the pack. But he made a critical mistake based on training methods of the time: he decided not to drink water during the race. He believed that drinking would slow him down, that it was a sign of weakness.

In 32-degree heat, this decision was catastrophic.

By kilometer 27, Kanakuri was in serious trouble. His vision blurred. His legs felt heavy. The heat was cooking him from the inside.

He saw a family in a garden near the course. They were having a party, drinking juice, enjoying the summer day.

Kanakuri stumbled off the course toward them.

The family—the Pettersson family—immediately saw that this young Asian man in running clothes was in distress. They offered him drinks. Orange juice. Water. Anything to help.

Kanakuri drank. One glass. Then another. The cool liquid felt like salvation.

The family invited him to sit down. To rest. Just for a moment.

Kanakuri sat on their sofa.

And then he fell asleep.

Not for a few minutes. For hours.

When he finally woke up, disoriented and embarrassed, the marathon was long over. The stadium had emptied. The race had finished without him.

Kanakuri panicked. He had failed. He had embarrassed Japan. He had traveled halfway around the world to compete in the first Olympic marathon for his country, and he had fallen asleep in a stranger's garden.

He couldn't face the shame of explaining what happened. So he didn't.

He quietly left Stockholm. He took a train. He traveled back to Japan without telling Swedish officials he was leaving, without withdrawing from the race officially, without explaining his disappearance.

To the Swedish Olympic Committee, Shizo Kanakuri had simply vanished during the race. One moment he was running. The next moment—gone.

They assumed he had gotten lost. Or collapsed somewhere on the course and wandered away. They searched but never found him.

For decades, Swedish Olympic records listed Shizo Kanakuri as a missing person.

But Kanakuri wasn't missing. He was back in Japan, trying to move on from his embarrassment.

He didn't give up on running. He trained harder. He competed again in the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp. Then the 1924 Olympics in Paris.

He never won a medal. But he kept running, kept representing Japan, kept pushing himself.

He eventually retired from competitive running and became a teacher, coaching and inspiring the next generation of Japanese runners. He married. He had six children. Ten grandchildren. He built a full life.

But the story of that 1912 marathon—the race he never finished, the mysterious disappearance—remained a strange footnote in Olympic history.

In 1962, fifty years after the race, a Swedish journalist named Claes Fellbom was researching Olympic history. He came across the strange case of the Japanese runner who had disappeared in 1912 and was never officially found.

Fellbom started investigating. He tracked down records. He followed leads. And eventually, he found Shizo Kanakuri—alive and well in Japan, now in his seventies, living a quiet life with his large family.

Fellbom contacted him. And for the first time, Kanakuri told the full story of what had happened that day in Stockholm.

The story was charming. Embarrassing. Human. A young athlete overwhelmed by heat and pressure, who fell asleep in a garden and was too mortified to explain.

The Swedish Olympic Committee learned about this and had an idea: Why not invite Kanakuri back to finally finish the race?

In 1967, fifty-five years after the 1912 Olympics, Shizo Kanakuri—now 76 years old—returned to Stockholm.

Swedish television filmed the event. They took him to the same neighborhood where he had stopped in 1912. The original Pettersson house was still there, now occupied by Agaton Pettersson's son.

Kanakuri visited the house. He met the son of the man who had given him juice that day. They talked about that summer day in 1912 when a confused young Japanese runner stumbled into their garden party.

Then they took Kanakuri to the Olympic Stadium.

The same stadium where the 1912 marathon had finished. Where 68 runners had started, and 37 had crossed the finish line—but not Shizo Kanakuri.

A finish line banner was set up. Cameras rolled. The crowd gathered.

Seventy-six-year-old Shizo Kanakuri, wearing a suit—not running clothes—walked across the finish line he had never reached as a young man.

When he crossed, he stopped the clock ceremonially.

His official time for the 1912 Olympic Marathon: 54 years, 8 months, 6 days, 5 hours, 32 minutes, and 20.3 seconds.

The longest marathon in Olympic history.

Kanakuri smiled for the cameras. When asked about his performance, he joked: "It was a long race. Along the way, I got married, had six children and ten grandchildren."

The audience laughed. The moment was joyful, absurd, touching.

This wasn't about athletic achievement. It wasn't about redemption or proving something decades later.

It was about closure. About finishing something left undone. About an old man getting to finally complete a journey he started as a young man full of hope and pressure.

Shizo Kanakuri died in 1983 at age 92. By then, he was celebrated in Japan not for setting records or winning medals, but for his persistence, his humor, and his story that reminded everyone that even Olympians are human.

He competed in three Olympics. He trained countless students. He lived a long, full life.

But what people remember most is the marathon he didn't finish in 1912, and the finish line he finally crossed in 1967.

Sometimes the story isn't about winning. Sometimes it's not even about finishing strong.

Sometimes the story is about a young man who fell asleep in a garden on a hot day, was too embarrassed to explain, and lived with that unfinished race for fifty-five years.

And then, as an old man, he got a second chance. Not to race. Not to compete. Just to walk across a finish line and say: I'm here. I made it. It took me fifty-five years, but I finished.

That's the beauty of Shizo Kanakuri's story. It's not about athletic glory. It's about being human—making mistakes, feeling shame, carrying regrets, but ultimately finding peace and humor in the absurdity of it all.

The longest marathon in Olympic history.

Finished by a 76-year-old man in a suit, walking to a finish line that had waited for him for fifty-five years.